gRasping the sentiment

TGIF project using popular songs

Getting the sentiment is about the most subjective activity there is. Yet, it’s surprisingly simple to get machine to do it. As a TGIF project, this post examines the sentiment of four popular songs from a rather diverse spectrum of genres - yielding sometimes predicted and sometimes rather surprising results

The first step toward getting this done is obtaining the raw data - i.e. lyrics. There is no need to type while singing along, Google has them readily available when searching for ‘<title> lyrics’. Though the algorithm can take any number of songs, I want to draw up some graphics and do some meaningful interpretation. So I constrain myself to four songs by three artists (in order of year of release):

- ‘National Anthem’ by Lana Del Rey

- ‘Power’ by Keyne West - parental advisory ;-)

- ‘Out of the Woods’ by Taylor Swift

- ‘Love’ by Lana Del Rey

I saved each song into one file, ending up with ‘nationalanthem.txt’ and so forth.

Now, it needs a little R code to do the actual analysis - starting with required libraries tm (as in text mining for stop words, etc.) and tidytext (for a sentiment dictionary). Plus, I need three global variables to hold the (static) collection of stop words, for collecting data from files and for the file names as such:

library(tidytext)

library(tm)

stp <- stopwords()

dfAll <- data.frame(sent=c(), cnt=c(), song=c())

s <- c('love', 'nationalanthem', 'outofthewoods', 'power')

Then, it’s all set for reading and analyzing files: The following code reads all of them line by line, and creates a data frame with a line for each word of a song text file

for(f in s){

natL <- readLines(paste(f, '.txt', sep=""))

nat <- tolower(unlist(strsplit(natL, "\\s|[,?\\.()]")))

df <- data.frame(table(nat))

I end up with df holding the count of each word - like this (excerpt):

nat Freq

5 abandon 1

13 baby 6

22 boy 2

The next step is to eliminate stop words words (like ‘the’, ‘and’, etc.) that don’t bear any sentiment or significance of their own:

dfF <- df[(df$nat!='' & is.na(match(df$nat, stp))),]

Now, only with ‘relevant’ words, I can attach a sentiment from a dictionary (tidytext provides one that’s ready to go). The dictionary maps words to sentiments like ‘anger’ or ‘joy’. As tidy text provides several dictionaries that overlap, I first take the max frequency (= min and any other) for each word before summing up:

dfF <- df[(df$nat!='' & is.na(match(df$nat, stp))),]

dfM <- merge(dfF, sentiments, by.x=c('nat'), by.y=c('word'))

dfMA <- aggregate(Freq~nat+sentiment, data=dfM, FUN=max)

dfAgg <- aggregate(Freq~sentiment, data=dfMA, FUN=sum)

colnames(dfAgg) <- c('sent', 'cnt')

dfM then contains plain words with sentiments - like this (excerpt):

nat Freq sentiment lexicon score

1 abandon 1 fear nrc NA

2 abandon 1 negative loughran NA

6 baby 6 joy nrc NA

7 baby 6 positive nrc NA

8 boy 2 negative nrc NA

Taking the max frequency and summing up, dfAgg contains a data frame with how often each sentiment appears (per song). I put one frame below the next:

dfAgg$song <- f

dfAll <- rbind(dfAll, dfAgg)

}

Now, dfAll contains the counts of all sentiments per song - but they’re in one flat list, like this:

sentiment Freq song

1 anger 15 nationalanthem

2 anticipation 29 nationalanthem

However, this is not a matrix of sentiment to song in one dimension and the song in the other, like this:

love nationalanthem outofthewoods power

anger 17 15 4 25

anticipation 14 29 6 13

so, I need to transpose:

dfDim <- data.frame(sent=unique(dfAll$sent))

for(f in s){

dfSlc <- dfAll[dfAll$song==f, c('sent', 'cnt')]

colnames(dfSlc) <- c('sent', f)

dfDim <- merge(dfDim, dfSlc, by=c('sent'), all=TRUE)

}

rownames(dfDim) <- dfDim$sent

dfDimM <- as.matrix(dfDim[,c(2:ncol(dfDim))])

So now, I’m done - yeah! There’s a matrix dfDimM ready to be plotted:

barplot(t(dfDimM), beside=TRUE, legend=TRUE, cex.names=0.5)

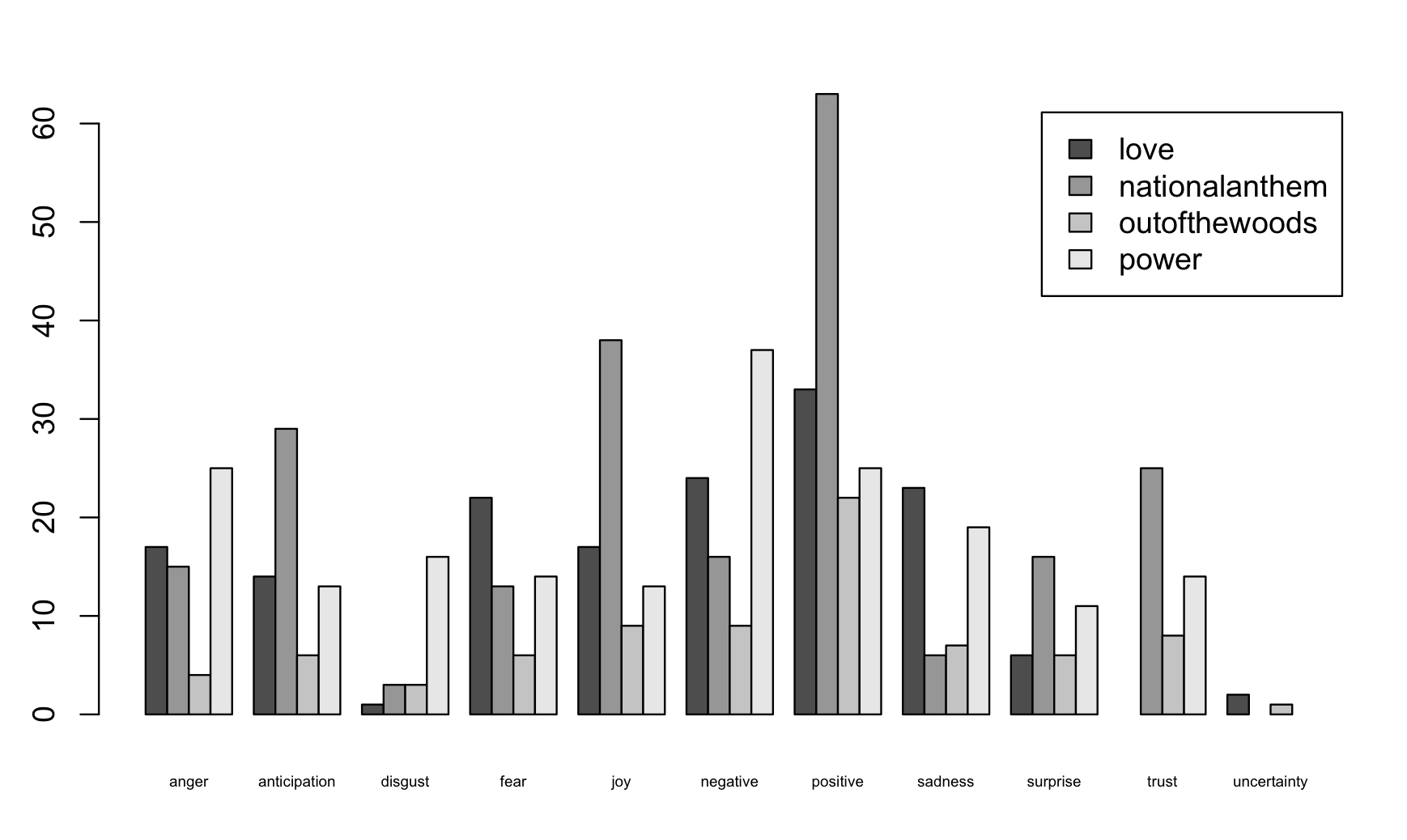

What comes out of this this diagram with how often each sentiment comes up per song:

There’s some chances of actually verifying the results - foremost by looking into df (raw word count) dfM (raw word 2 sentiment rount), dfAgg (count of sentiment) and dfDimM (the numerical result) - preferably for one song first. Each stage is quite transparent - and errors (like double-counting words from two dictionaries) come up.

What springs to mind when taking a step back: The more blunt the song is, the better the resulting graph seems to match (at least my) subjective view of what a song’s sentiment is. ‘Power’ is openly angry and negative - and the algorithm gets it quite well. By contrast, the between-the-lines sadness of ‘National Anthem’ is lost to the algorithm to quite some extent. As the computation looks at the individual words only (what is obviously there), ‘National Anthem’ is rated the most joyful and positive piece of art out of all the four - by a wide margin - although one can doubt that very much when actually listening. Subtlety falls through the cracks. A less extreme song like ‘Out of the Woods’ scores average on the sentiment scale - which does fit (not that it’s better or worse - it just captures sentiment pretty well).

All overall, it’s surprisingly simple to get the basic sentiment of a text - not down to the last detail, but basically pretty well. Outside of TGIF, there certainly are use cases for this - like classifying incoming e-mails by sentiment to figure out which are worth an especially quick answer. As e-mails are not as artsy as songs, and thus probably more to the point, the accuracy is likely even better in that case. Anyways: tooling is there.

The full script is available as gist - feel free to try out and let me know what you think!

P.S.: advanced text analysis

Roughly one in three words in above songs actually has some sentiment. All others are simply ignored. I could dive into things like stemming (there’s methods for this in tm) - however, when looking at the words not assigned (like ‘back’, ‘cruising’, ‘go’, ‘just’, ‘kids’), there doesn’t seem to be a lot of value in assigning sentiments in the first place. Still good to know I don’t really miss out on anything. And depending on use case, a little extra effort might still be required.

P.P.S.: subtlety throws the best

To check how other implementations cope with subtle texts, I tried Microsoft’s text analytics service (there is an online playground) with ‘This is amazing’ (marked positive), ‘It sucks’ (marked negative) and ‘Amazing to see how people keep trying to achieve what my cat could do while asleep’ (marked positive). So, they struggle with the phenomenon, too. And, if it’s really true that stronger e-mails get looked at preferably then one would have to become very blunt or very sarcastic to be read at all :-(